I didn’t expect finding AI music datasets to be so difficult, but there I was, scrolling through countless research papers and online resources. My goal seemed simple – to create a machine learning model that could understand and generate music, maybe even compose pieces that sounded like a human played the piano. The real challenge, though, was tracking down the right data to get started.

I needed datasets for a few key reasons. To start with, my project used supervised learning, so labeled audio was essential - music marked with details like genre, instruments, tempo, key, and ideally mood. Without this kind of structure, the models would struggle and produce messy results that sounded more like noise than music. On top of that, variety was important to me, since a wide range of sounds helps models learn better.

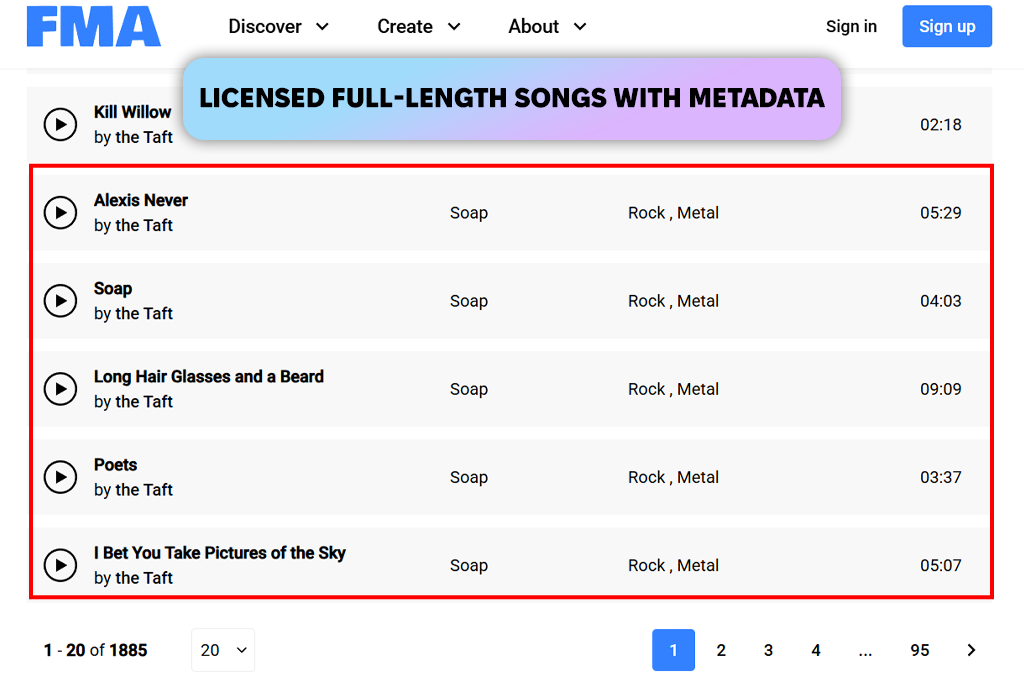

Music comes in so many forms like pop, jazz, rock, folk, electronic, and beyond. For my model to work well, it needed to learn from a wide range of styles to identify patterns that could apply to any genre. Also, the datasets had to be legally safe to use. I couldn’t afford to use copyrighted material without permission, so I focused on open-source or Creative Commons-licensed options.

To avoid getting overwhelmed, I reached out to my colleagues at the FixThePhoto team for help with the testing, since they have experience with image datasets. We teamed up, created a list, and began thoroughly exploring music datasets for machine learning.

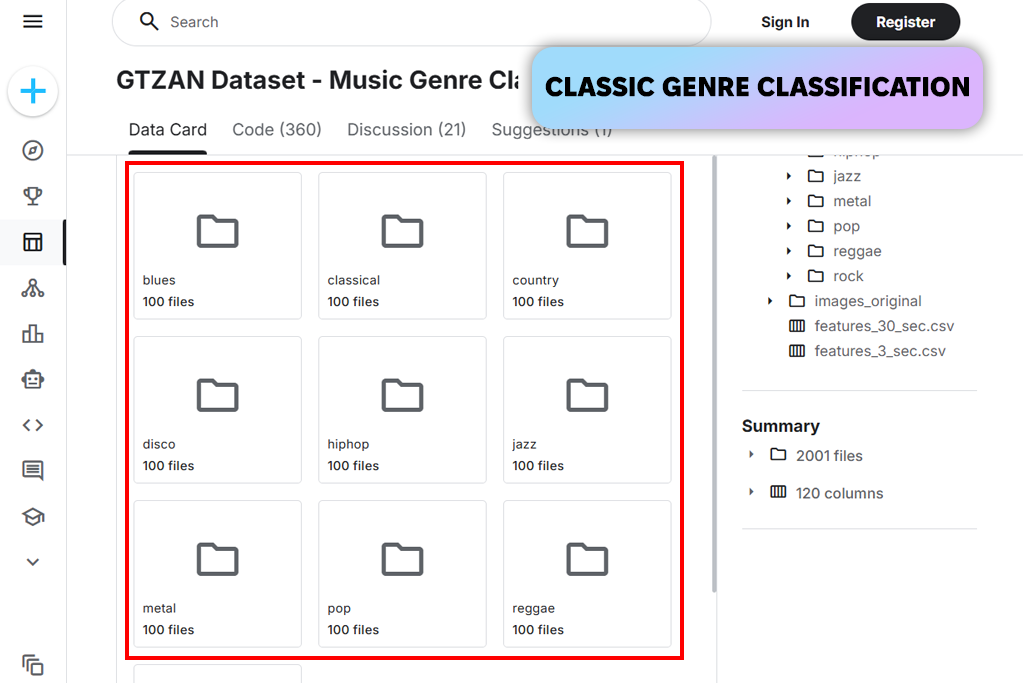

I began my search in the usual spots: sites for developers, researchers, and data scientists. The first thing I found was the Million Song Dataset. It sounded huge and impressive, but it only contained data about the songs, not the actual music files I needed for my AI model. Next, I looked at the GTZAN genre collection. It was smaller, simpler, and popular in studies. However, I kept hearing it had flaws, like wrong labels, duplicate clips, and an uneven mix of music styles.

After a week of looking, I made a shortlist of three sources: the Free Music Archive, Magenta's NSynth dataset, and the Lakh MIDI Dataset. Each had a different compromise. The Free Music Archive had the actual music files and song details, but its collection leaned heavily toward specific music styles. The NSynth dataset provided very clean recordings of single notes, ideal for AI that creates sound, but it did not include any finished songs. The Lakh MIDI Dataset was excellent for training AI on musical patterns, but to get actual sound from my model, I would need to turn the MIDI note data into audio files.

Things got tricky quickly. Some music collections had missing or broken songs. The information about the songs wasn't organized the same way - one set listed the speed with a number, another used words like "slow" or "fast." Figuring out the legal rules for using the music was confusing, and I had to double-check everything even if it seemed free to use. Then there was the problem of space; storing all that music began to overload my laptop and my internet.

Music datasets for machine learning are groups of music files (like MP3s), sheet music data (like MIDI files), and song information. These datasets are what teach AI to recognize patterns in music. They are the basic material needed to train a computer to analyze, understand, or even make new music with music producing apps.

The process of using them has a few main steps, which are essentially the same across the board:

Music training datasets are the foundation for many machine learning tasks, from analyzing and classifying music to creating new compositions. Their use can be divided into two main areas: music analysis and music generation.

1. Music analysis

Music analysis includes all tasks where a model learns to understand existing music.

Classification and tagging. The goal is to automatically identify a track’s genre, mood, tempo, or instruments. Models are trained on audio and metadata (such as genre, mood, tempo, and instrumentation) and then used to predict these labels for new tracks. This is commonly used in:

Emotion analysis. Models predict the emotional tone of a track (happy, sad, calm, etc.). This is used in music therapy, interactive soundtracks, and personalized recommendations.

Feature extraction and music analysis. Datasets make it possible to extract spectral, rhythmic, and harmonic features, which can be used for classification, clustering, or academic research in music studies.

2. Music creation

This area focuses on generating new music or transforming existing tracks.

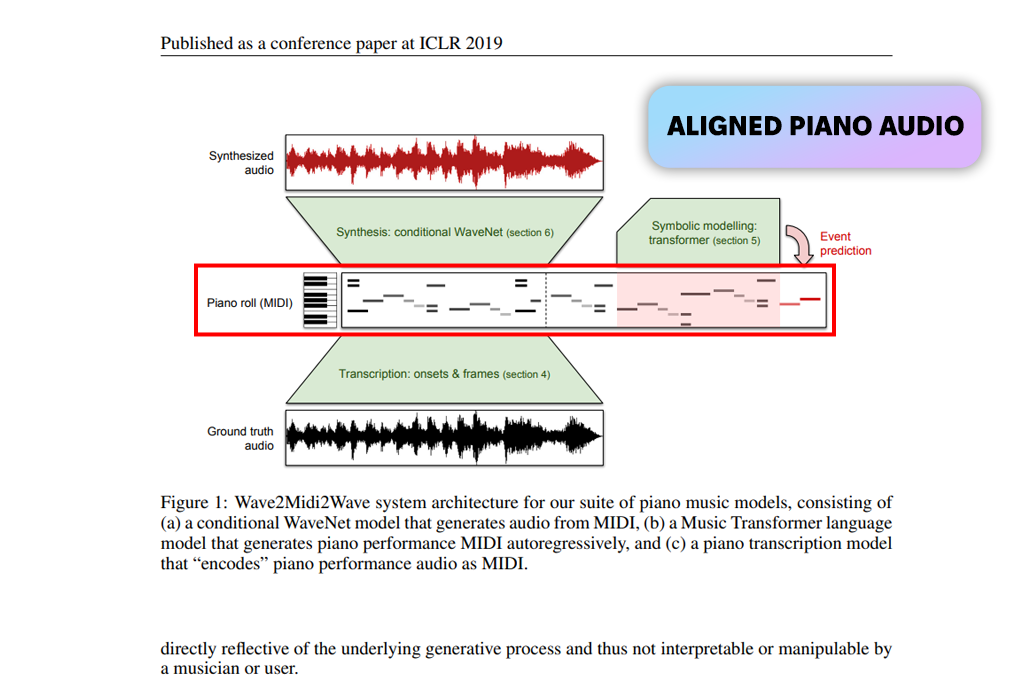

Music generation. Models are trained on MIDI, audio, or symbolic formats (such as piano rolls) to create new pieces of music. The choice of format depends on the type of model being used:

Music transcription. The goal is to convert audio into notes or chords. This requires datasets with accurate labels for notes, timing, and dynamics.

Source separation. Models are trained to split a mixed track into separate parts, such as vocals and individual instruments. This requires music datasets where full mixes come with isolated stems. It’s commonly used for karaoke, remixes, and music analysis.

3. How to work with music datasets

For any task, there are several key steps to follow:

Model selection and training:

Evaluation and improvement

I first used MUSAN not to create music, but to make my audio AI stronger. I needed everyday sounds like background noise, music, and people talking to train my models for real-world use. MUSAN worked perfectly for this. Adding it to my training process quickly made my models perform better in new situations. It became a very helpful, secondary resource.

The limitation was clear from the start. MUSAN doesn't include structured music, a wide range of genres, or helpful labels. It can't teach an AI about chords or beats. I only used it as a practical tool for sound, not as a source for learning music itself.

GTZAN was the first dataset I tried, since it was in every tutorial. It was small, simple, and great for testing my basic code. My early tests ran quickly and gave me clear results. Back then, GTZAN was a very easy and helpful starting point.

Over time, I found serious problems. The dataset had duplicate songs and wrong labels, which messed up my results. It also didn't have enough variety in music styles, and some clips were confusing. In the end, I stopped using this artificial intelligence software for my final projects. I only kept it around for basic tests and demonstrations.

FMA was a major step forward for my work. It gave me real audio files with clear Creative Commons licenses and detailed metadata. The option to choose between different AI music dataset sizes made it easy to start small and grow my experiments, which worked well for both quick tests and bigger models.

The main drawback was uneven data. Some genres appeared far more often than others, and the metadata wasn’t consistent across tracks. I had to spend a lot of time cleaning everything before I could train models I trusted.

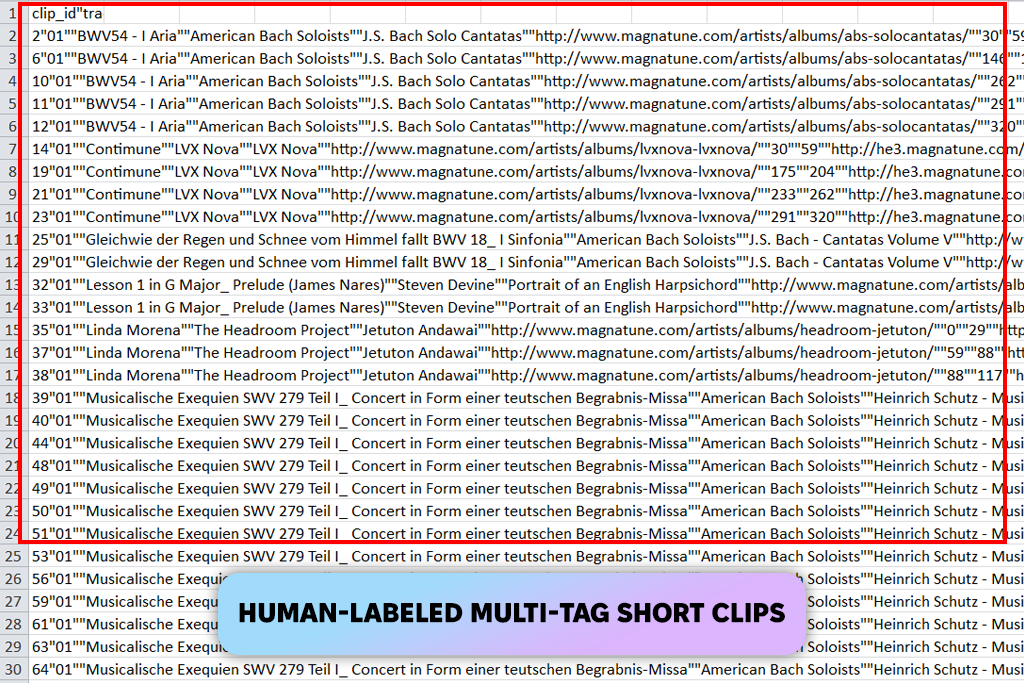

I used MagnaTagATune when I needed tracks with multiple labels. It helped my models learn more detailed traits beyond genre, like mood and instruments. Since the tags were added by people, they captured details that automated labels usually miss. It worked especially well for tagging tests without relying on extra music management software.

I quickly began to appreciate the MAESTRO music dataset for deep learning. The exact alignment of the audio and MIDI files made my music transcription experiments very reliable. The expressive piano recordings gave a realistic quality that helped my sequence models learn better. I had complete confidence in the accuracy of its labels.

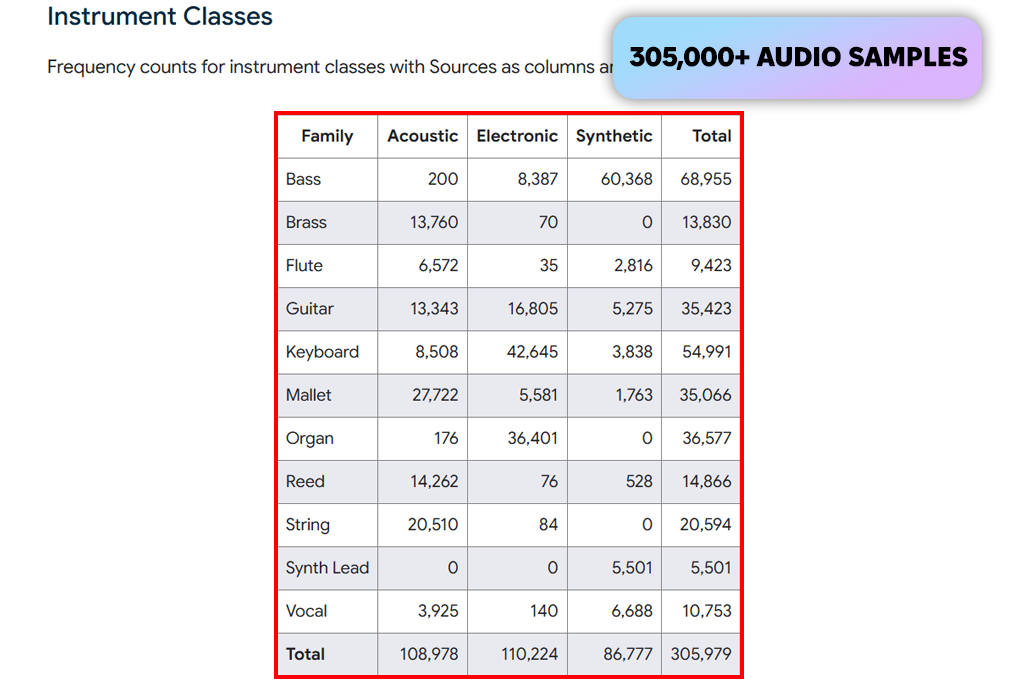

The NSynth dataset changed how I work with sound. Its clear, single-note samples with reliable labels let me model different tones precisely. This made it perfect for teaching AI the unique qualities of each instrument. It was especially effective for use with audio-based generative AI https://fixthephoto.com/best-generative-ai-tools.html (Best Generative AI Tools List) tools.

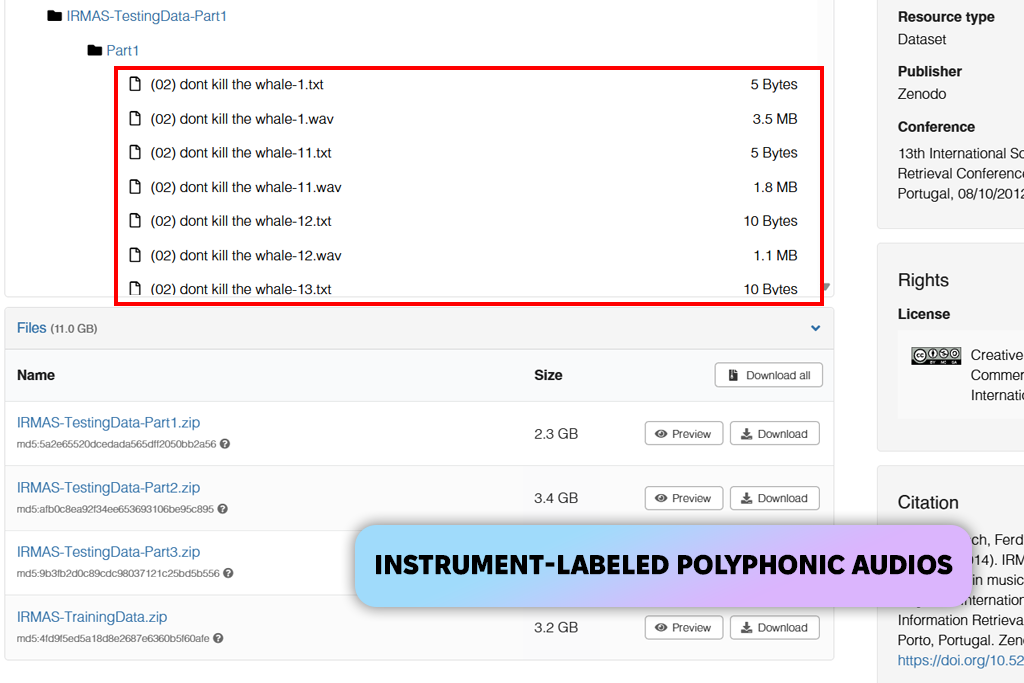

I found IRMAS very useful for testing instrument recognition. Its clear labels for the main instrument in a track were great for supervised learning. This let me accurately test classifiers that work by identifying an instrument's unique sound. The training process was straightforward and worked well.

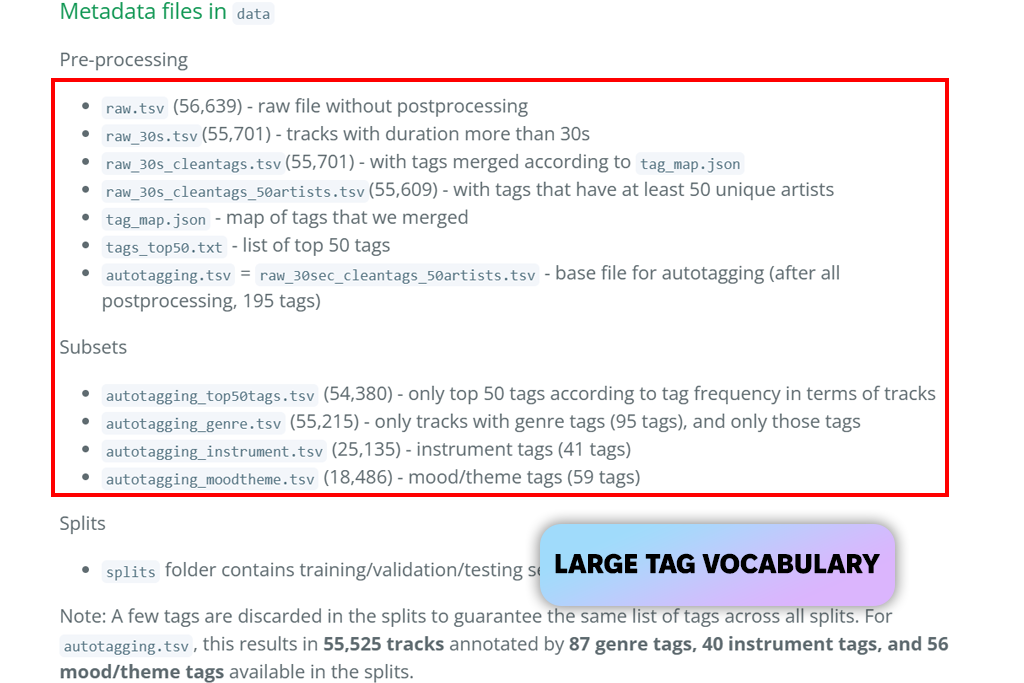

MTG-Jamendo gave me a good mix of large size and solid annotations. The clear licensing meant I could safely use it for both research and demos. With tags covering genre, mood, and instruments, it turned into one of the most flexible datasets I worked with.

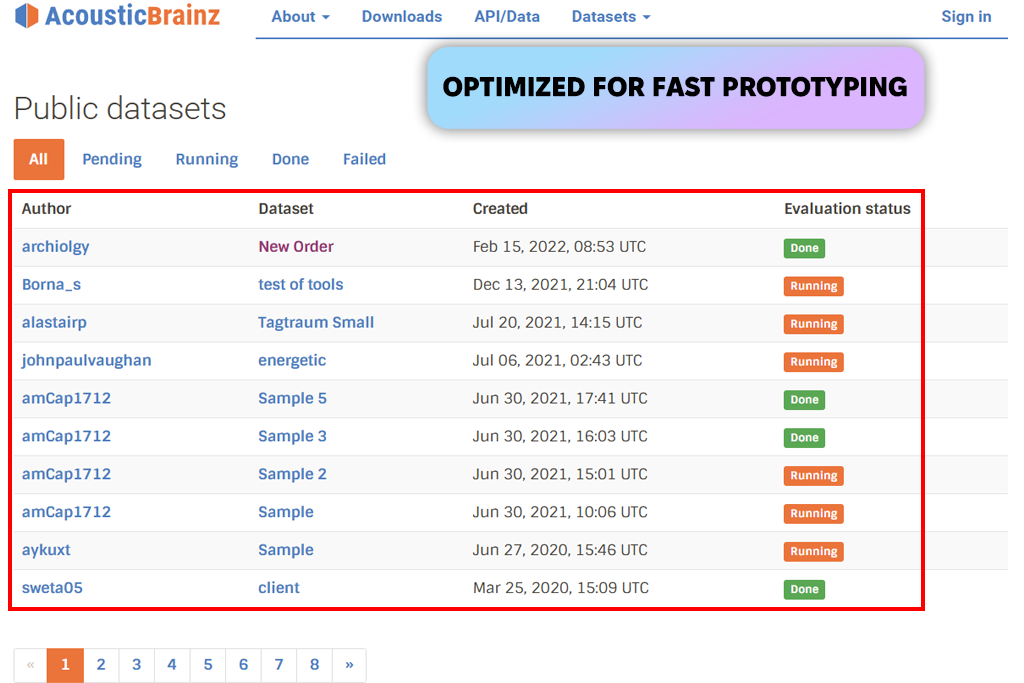

AcousticBrainz helped speed up my early experiments. Since the audio features were already prepared, I didn’t need to spend time on heavy preprocessing. It worked especially well for quick tests with classifiers and clustering, and the consistent features made everything easier to manage.

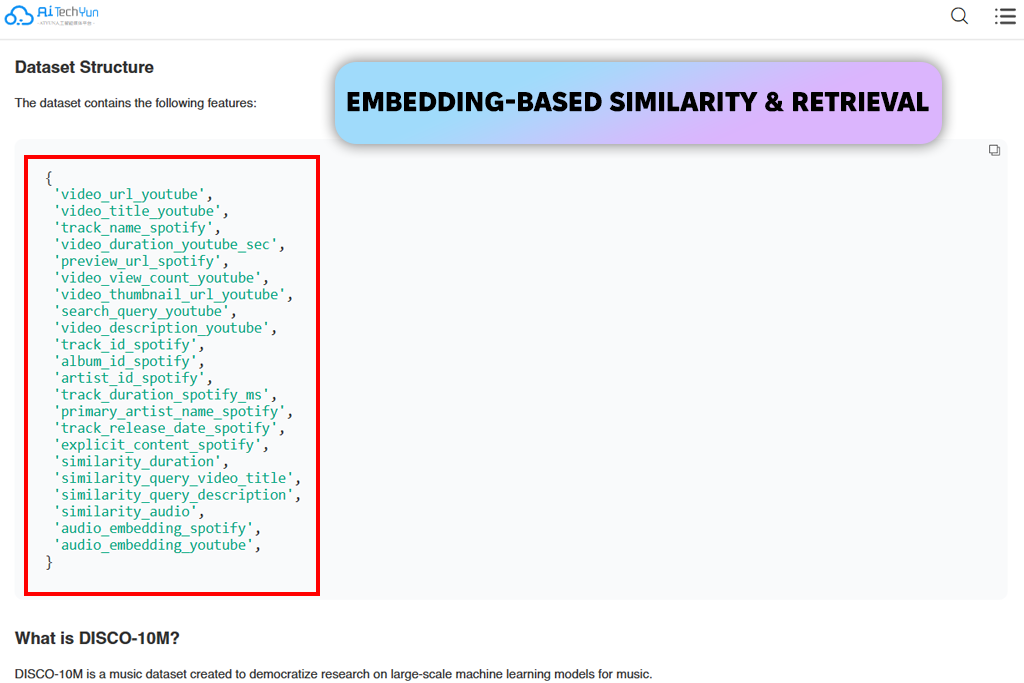

I was really impressed by the huge size of DISCO-10M. The ready-made audio features it provided let me do searches for similar sounds and retrieve tracks right away. This meant I could run experiments without needing costly training. It was particularly helpful for my work on music recommendation systems.

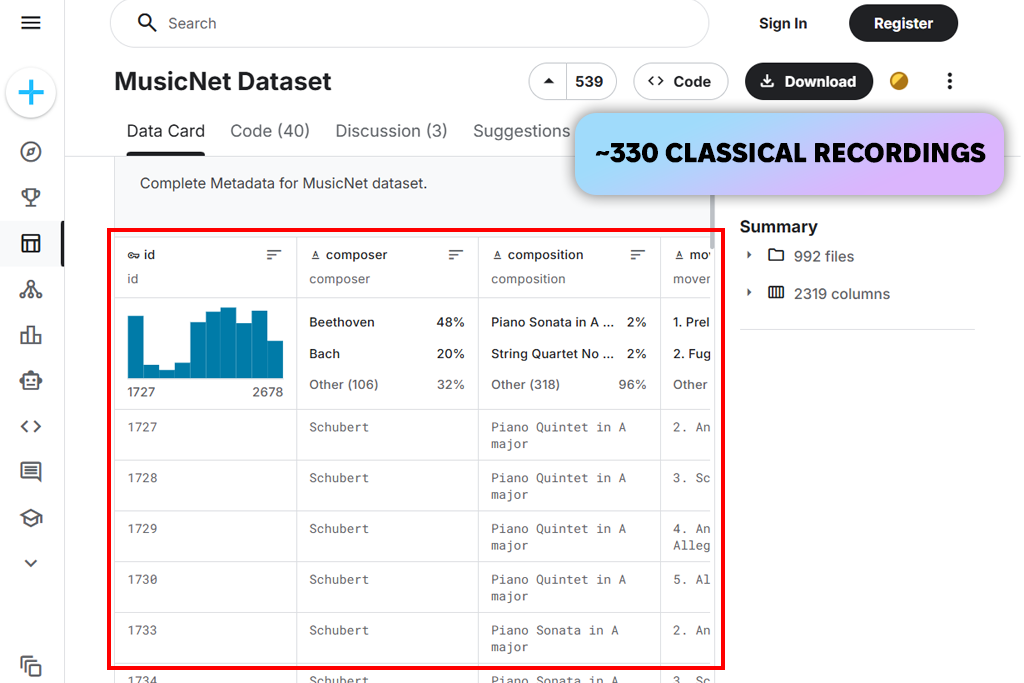

MusicNet provided very detailed annotations. Each note was labeled clearly, which made accurate transcription models possible. The classical recordings added richness and complexity to the music. Overall, this music training dataset made careful and reliable evaluation possible.

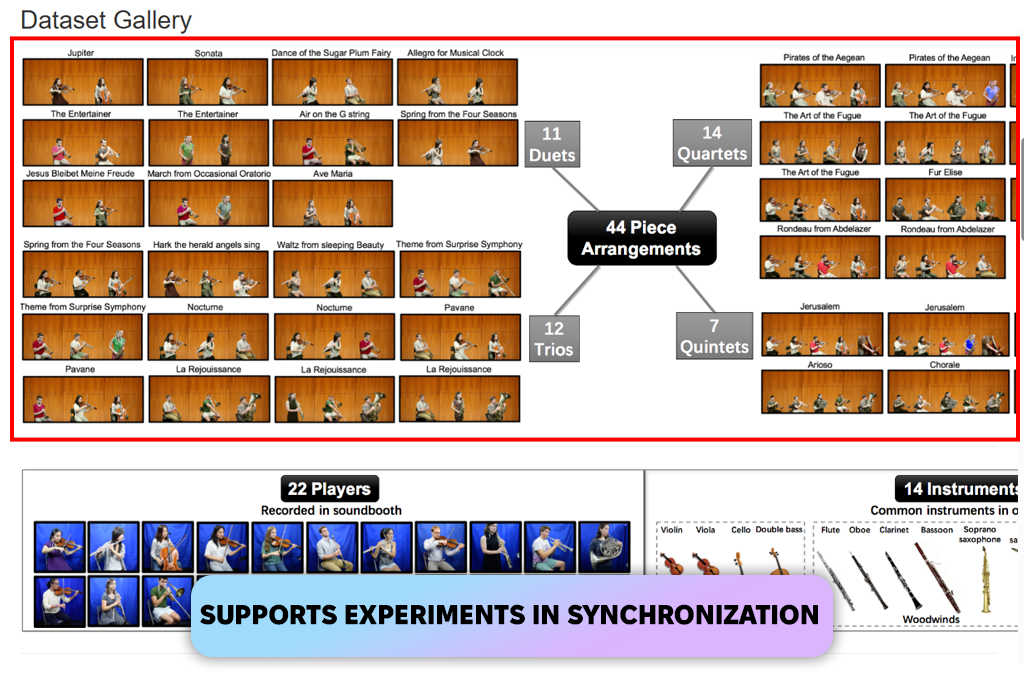

I liked URMP because it combined audio, MIDI notes, and video perfectly. This made it great for studying groups of instruments, testing how to sync different parts, and modeling performances. It felt like a very well-made music dataset.

Tabla Solo introduced me to complex rhythms from outside the Western tradition. Its precise annotations helped me model detailed timing patterns. This really broadened my approach to rhythm. The whole dataset felt rich with cultural meaning.

Our FixThePhoto team, including Eva Williams, Kate Debela, and Vadym Antypenko set out to carefully test a variety of music datasets. Our aim was to check more than just how big or clean they were. We wanted to see how useful each one really is for common tasks like sorting music by genre, detecting its mood, labeling it with tags, or creating new music from symbols and patterns.

We began by choosing a balanced set of well-known datasets, including GTZAN Genre, Free Music Archive (FMA), MagnaTagATune, MAESTRO, NSynth, MTG-Jamendo, MusicNet, and Slakh2100. The first step was preprocessing the data: we converted all audio clips to the same sample rate, normalized them, and in some cases turned them into spectrograms or MFCC features for deep learning. For symbolic datasets such as MAESTRO and GiantMIDI-Piano, we transformed the MIDI files into piano rolls and note sequences.

Eva Williams tested music datasets to help computers identify genres and tags. She used two main sets of data: GTZAN and FMA. The FMA set was bigger and more detailed, so her computer learned better and made more accurate guesses about a song's genre.

The GTZAN set had mistakes, like repeated songs and wrong labels, which made it less reliable. She also used the MTG-Jamendo dataset. First, she had to clean up its list of tags. After that, her computer became very good at identifying multiple tags for a song at once.

Kate Debela focused on making computers create music. She used two main music collections to teach them. The first, called NSynth, helped the computer learn to make brand new, realistic instrument sounds. The second, MAESTRO, helped it learn to compose expressive piano music, though it only learned piano style. She also used a drum dataset called Groove MIDI. This taught the computer to make drum beats that sound like they were played by a person.

Vadym Antypenko worked on two main tasks: separating instruments and writing down music notes. To separate instruments, he used special music libraries called Slakh2100 and AAM. These contain mixed songs. He taught his computer program to pick out single instruments from the mix, like isolating a piano from a band. His program learned this task very well and worked almost perfectly in practice. To transcribe music, he used a dataset called MusicNet.

Getting it ready took a lot of work, but once he did, his computer could very accurately listen to music and write down the notes that were played. These notes were then very useful for studying the music's patterns.

As a team, we combined quantitative metrics with qualitative listening tests. For example, we evaluated the musicality of piano sequences generated from MAESTRO and judged the natural feel of drum patterns from Groove MIDI. In classification experiments, FMA consistently achieved higher accuracy than GTZAN, while MTG-Jamendo produced more nuanced and reliable multi-label predictions.

NSynth and Slakh2100 delivered excellent results for synthesis and source separation. However, Vadym noted that models trained only on this synthetic data showed a noticeable drop in performance when tested on real recordings.

Overall, our testing process at FixThePhoto gave us a clear picture of what each music dataset is best for. We found that GTZAN and CH818 are convenient for quick, early tests.

FMA and MTG-Jamendo excel at tasks like sorting music by genre or applying multiple tags. MAESTRO and NSynth are top choices for generating new music, while Slakh2100 and AAM are strongest for source separation.

Eva, Kate, and Vadym carefully documented all their results to create a practical guide to help anyone choose the right music dataset for their specific machine learning project.