We can learn a lot about photography by studying the works of masters like Henri Cartier-Bresson, known for his focus on capturing decisive moments and influenced by surrealism.

After studying some of Bresson's photos, I've put together tips inspired by how he used dynamic symmetry and geometry. These tips can help you recreate the signature style of this famous photographer.

Diagonal composition arranges elements along diagonal lines in the image. The golden triangle involves diagonal lines forming right-angle triangles to guide photography composition. Imagine a scene where a subject lies along a diagonal line. Another line intersects it at one-third or two-thirds of its length, where the most interesting part of the image should be.

If you look at the photo below, you'll notice how diagonals intersect precisely on the person's face, showcasing a Henri Cartier-Bresson composition. This makes the image more interesting than if the figures were in the center of the frame.

This method focuses on making the subject stand out from the background. You achieve this by contrasting bright subjects against dark backgrounds or dark subjects against light backgrounds, a hallmark of Henri Cartier-Bresson's composition.

Placing the main subjects on opposite sides of the image helps create balance. Using different shades of black and white or other contrasting colors also helps achieve this effect.

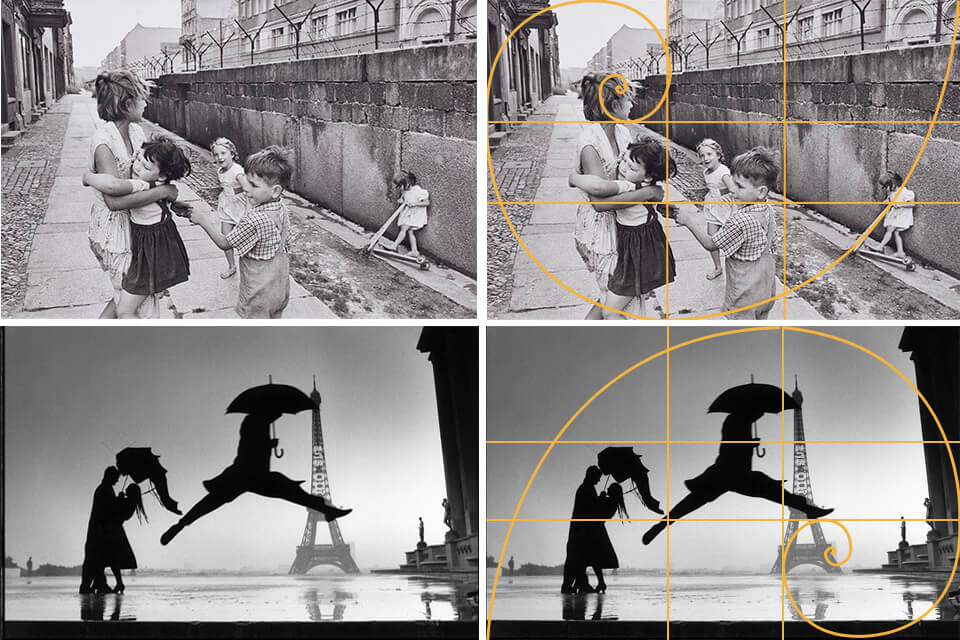

This method uses a sequence of numbers called the Fibonacci sequence. The ratio of 1:1.618 creates a growing spiral. You don’t need to be a math expert to use geometry in your photography.

All you need to do is learn the spiral and its eight positions in your images. Place the most interesting parts of your scene at the intersections.

Look at Bresson’s photo of the Bolshoi Ballet School. Multiple ballerinas stand in the same position, creating a repetitive pattern. This repetition in photography makes the photo more interesting.

Shadows can add shapes, forms, and textures to a scene, creating an overlay within the frame. They offer two scenes in one photograph. For example, in this image, besides the cat on the chair, there is also a person's shadow, which adds a new dimension to the frame.

To capture shadow photography, choose objects or people with interesting shapes. The best times for such photos are early morning or late afternoon when you can get dramatic shadows.

For these photos, I use a low ISO, narrow aperture (high f-stop), and fast shutter speed. I also like to experiment with different shooting angles to see how shadows change and interact.

I found the concept of "the decisive moment" fascinating. Henri Cartier-Bresson had a skill for capturing the perfect moment in every scene he photographed. He carefully timed his shots and composed them with elegance, making them seem effortless. When he spotted an interesting scene, he would take many photos, sometimes more than 20, to get the best shot.

One of Bresson's famous photos shows a man jumping into a puddle. I wondered what would have happened if Bresson had taken the photo a few seconds later. Would the man have landed in the puddle? What we do know is that the man was brave enough to try.

Photography is about capturing moments as they happen, a key Henri Cartier-Bresson composition lesson. A photographer's greatness lies in their ability to capture the perfect moment, just as Bresson did in his work.

Henri Cartier-Bresson wasn’t interested in "staged photography." He loved capturing natural, unposed photos. He said, “'Manufactured' or staged photography does not concern me. I judge it only on a psychological or sociological level. Some people take photos they set up beforehand, while others go out to find and capture the image.”

Early films inspired him a lot. He admired movies like "Mysteries of New York" with Pearl White, D.W. Griffith’s "Broken Blossoms," the early films of Stroheim, "Greed," Eisenstein’s "Potemkin," and Dreyer’s "Jeanne d’Arc." These films deeply impressed him, as he often mentioned.

He could capture scenes in beautifully composed frames. The more I look at his photos, the more I appreciate their perfection. He had a talent for composing and shooting without cropping, using only film cameras. He cared about the entire picture, not just the moment or what was in it. He searched for lines, curves, shadows, and shapes throughout the frame.

He never cropped his photos, with one exception. He once cropped a photo of a man jumping over a puddle because he was shooting through a hole in a fence and couldn’t get closer.

A valuable Henri Cartier-Bresson composition lesson I learned is to rely on cropping, as it can make you lazy. Try to get it right in the camera, but don’t reject a photo just because you had to crop it a little.

I recommend shooting from your gut or intuition. Don’t overthink it. Use the "fishing technique" in street photography by seeking out leading lines and waiting for your subject to come into the frame where you want them.

Review your photos after shooting to analyze your composition. It's important to see where you might have gone wrong and learn from it. Use this information to improve your compositions the next time you take photos.