I didn’t think about pitting the human eye vs a camera to see what makes them different until I was tasked with retouching a Northern Lights photoshoot. A photographer from our company took pictures of this mesmerizing event, and when I first saw the RAW images, their colors looked so crisp and saturated that they almost felt artificial.

However, that's not how they appeared to us in person. I was witnessing the Northern Lights next to my coworker, Tetiana, and asking myself: Why is the picture so much brighter and more colorful than real life? That day prompted me and the FixThePhoto team to discover how northern lights are seen by the human eye vs a camera.

| Feature | Human Eye | Camera |

|---|---|---|

|

Focal Length

|

~22–24mm feel

|

35–50mm standard

|

|

Megapixels

|

~576 (center)

|

24–100+

|

|

Dynamic Range

|

~20 stops

|

Up to 15 stops

|

|

Low Light

|

Weak colors

|

Longer exposure helps

|

|

Field of View

|

~180° total

|

Determined by the lens

|

|

Focus

|

Instant shift

|

Autofocus needed

|

This is one of the most prominent examples that allow making a camera vs human eye comparison. To our eyes, the northern lights had a subtle shimmer and were largely white and green. However, the camera captured vibrant greens, purples, and even reds when shooting with a 10-second exposure setting. The human eye is incapable of capturing so much light within a short timeframe, particularly during dark hours.

This led to the question: is the image fake if the camera can capture more than our eyes? The answer depends on the context. From a scientific point of view, the camera produces a realistic result. However, to make the photo reflect what a human can see, you'd need to reduce the contrast in saturation in image editing software.

Pro tip: If a picture looks empty and doesn’t have the stars you saw yourself, consider applying some free star overlays to subtly light up the sky. However, you need to ensure the added stars fit the perspective and lighting for a realistic looks.

We were constantly asking ourselves this question. Certain research states that the human eye has a focal length of around 22 millimeters, but this value covers peripheral vision and isn’t a factual reflection of how a person perceives the environment. In reality, our vision is closer to mimicking a 50mm lens in terms of depth, proportions, and background compression.

When pitting a 50mm camera lens vs the human eye, you'll notice that the photos taken with such a lens will be perceived as the most natural by the average viewer. There's no distortion and the perspective matches our vision when looking straight ahead.

Hence why most photographers, particularly newbies, are recommended to get a 50mm prime lens as their first one since they’re easier to get used to than an ultra-wide or telephoto model.

Meanwhile, lenses below 35mm start to exaggerate space and distort objects closer to the edges of the shot, which isn't a quality that the human eye is known for. Lastly, telephoto models compress distances, which is also drastically different from our vision.

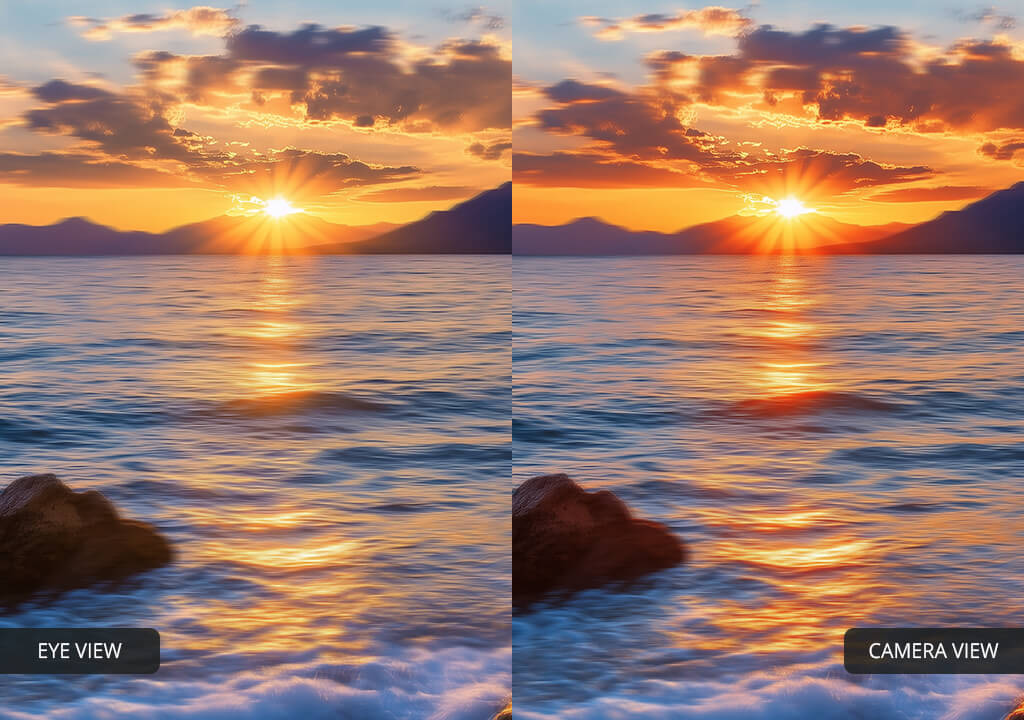

If there’s one area where we win the digital camera vs the human eye battle it's adaptability to shadows and highlights, which are often a big challenge to sensors. I experimented with this aspect during an indoor photoshoot. The model was near a bright window, and I wanted to have both the outside world and the room be adequately exposed. I was recreating one of the most reliable indoor photography ideas, leveraging natural lighting to create a balanced, flattering portrait.

However, my camera produced either blown-out highlights or an overly dim interior. Only HDR bracketing allowed me to rectify that issue, but the transition still didn't feel as natural.

This is the main difference in the dynamic range of the human eye vs a camera. Our eyes can recognize about 20 stops of dynamic range, while the leading full-frame cameras can handle 14–15. Our brains navigate the scene in real-time, mixing light and shadow on the fly. Meanwhile, the camera simply captures static exposure.

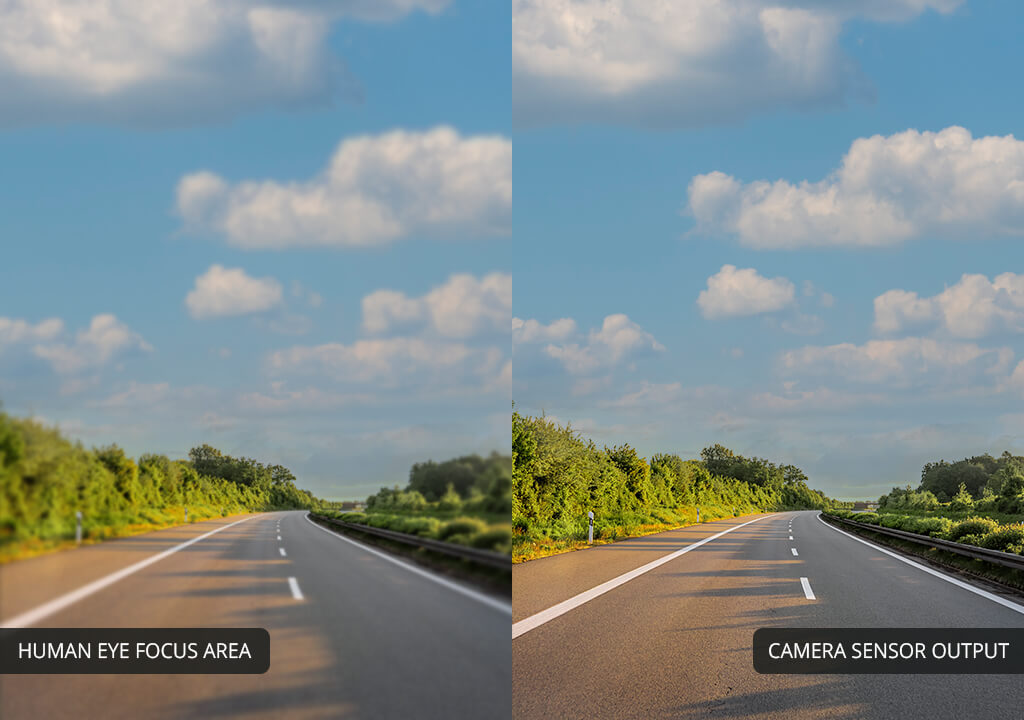

Resolution is also a frequently misunderstood concept. Certain research places the central vision of our eyes at 576MP, but that sharpness is only relevant for the point we’re focusing on. The rest of the scene is significantly blurrier. While the overall megapixel count is incredible, it doesn’t pertain to the entire scene.

Meanwhile, a camera can produce even sharpness across the entire shot. A 45MP offers only 10% of what the human eye can do, but it focuses on the entire shot simultaneously without having to resort to continuous focus shifts. From a certain point of view, the camera can see more, but it doesn't have the adaptability of our eyes.

Cameras produce even sharpness across the entire show, particularly if you're using a professional lens. However, our eyes work differently, as they can only keep a limited area in our vision sharp – the fovea. Everything else we see is blurry and has a "lower resolution", even if you're unaware of it.

Additionally, our brain tweaks the exposure in real-time. If you glance at someone standing near a bright window, your eyes will instantly balance the powerful outdoor lighting with the darker interior. Meanwhile, my camera needs assistance and it can only stick to one exposure setting at a time, which tends to create blown-out highlights or overly dark shadows.

I once had to take photos of a big window facing the sun for a real estate listing. While everything looked properly visible to my eye, the images ended up having either a blindingly white sky or extremely dark walls.

The human eye dynamic range is superior to a camera’s, which is why you’ll often find real estate photography tips that recommend doing exposure bracketing, which is the only method for recreating what our eyes see in such challenging shooting conditions.

If you put a camera vs the human eye, you’ll notice that they don’t operate the same way. Our eyes scan, adapt, and put together a cohesive image over time, while the camera immortalizes a single static moment. Here are some typical examples that highlight the difference between our vision and a camera.

What the eye sees: Balanced scene that combines the bright outside world with a dim interior.

What the camera captures: Either the sky outside is blown out or the interior is extremely dark.

What the eye sees: Limited brightness, soft glows, subtle shadows.

What the camera captures (long exposure): Vibrant neon hues, starburst lights, more detail than perceived by your sight.

What the eye sees: Fluid transition from the glowing sky to the dark ground.

What the camera captures: Either an overexposed sky or an underexposed landscape.

Eye: Instinctively focuses on the face, background appears blurry.

Camera: Based on the aperture, the backdrop can look overly sharp or soft.

From the start, the way we constructed cameras was founded on the principles of our eyesight. The lens bends lighting akin to the cornea, the aperture tweaks brightness like the pupil, while the sensor functions similarly to the retina. Even the term “focus” stems from our vision system.

However, even though a camera can imitate the structure, it can't recreate the intricacy of human eyesight. Our vision adapts in real-time, continuously evaluating the scene and transmitting detailed data to our brain without any manual effort on our part.

That said, when drawing a human eye vs camera comparison, you can notice that both employ aperture and depth of field to control what area remains in a scene. A wider aperture leads to a shallow depth of field, blurring the backdrop, similar to how our eyes can focus on a single face in a crowded place.

Nowadays, cameras still strive to offer a more accurate recreation of what our eyes see. The AF systems focus on eyes and faces by default. Exposure systems employ AI to balance the shadows and highlights, while HDR attempts to imitate how our vision naturally tackles contrast.

However, a camera still captures individual moments while our vision performs all the aforementioned tasks instantly and constantly.

This explains why even premium cameras can have issues taking photos of sunsets, bright windows, or dark rooms. While our eyes might perceive a balanced scene, the image taken by the camera might require some post-processing work done after. The market frequently introduces better sensors, but they still can’t match our eyes. As for image retouchers and photographers, the fuller understanding of human eyesight you have, the more knowledge you can apply when trying to compose, frame, and enhance your photos.

We tested how various focal lengths stack up against the human eye by taking pictures of the same scene while switching between 24mm, 35mm, 50mm, and 85mm lenses. We picked a spot, snapped the photos, and then evaluated them as a team. We wanted to know which lens would provide a result that would be closest to our sight on a hypothetical human eye vs camera diagram.

Our conclusions:

When examining the 50mm photo, we reached a consensus that it’s the most natural replication of how we saw the scene, as it didn’t exaggerate or compress any details.

That’s why we pick a 50mm lens whenever we want to take a portrait or street photo that can help convey our vision of the scene. While the focal length of such a lens is different from that of the human eye – the impression you get as a viewer is what’s most important.